14 Essential Quotes from 1984

Studying 1984 for the Common Module? You’re in the right place.

We’ve pulled together 14 essential quotes that capture the core anxieties of Orwell’s novel: the pervasive surveillance, the manipulation of truth, and the fragile struggle to “stay human” under the constraints of a rigid totalitarian regime.

For each quote, we unpack the techniques, meaning, and how it links to key Common Module ideas like:

the shaping of individual and collective identity,

the power of language and representation,

and the complex, sometimes terrifying human experiences created by oppressive systems.

If you want to write confidently about 1984 in your Common Module essay, these are the quotes you NEED to know inside-out.

Lets get into it.

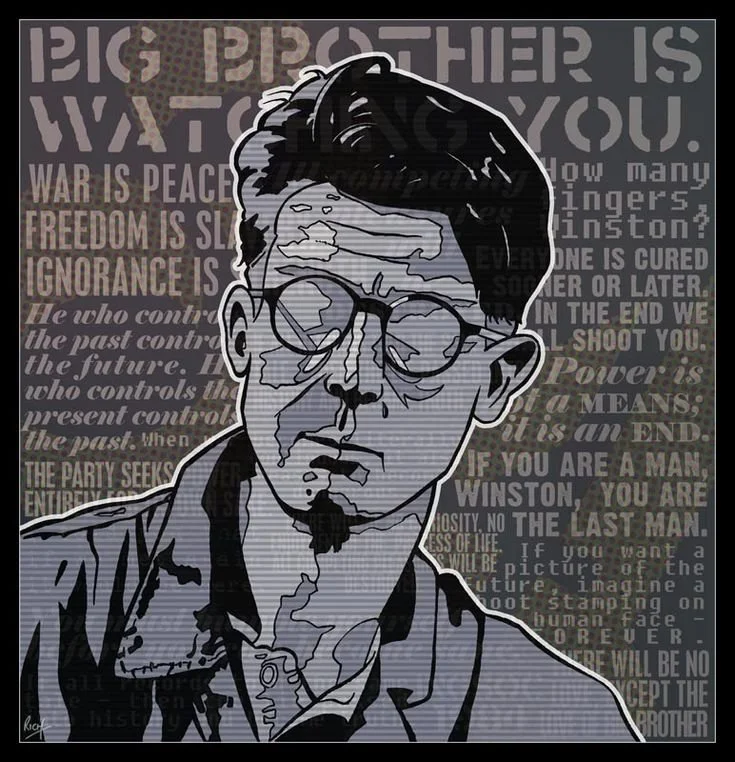

‘The eyes follow you about when you move. BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU’

The constant surveillance symbolized by the “eyes” emphasizes the Party’s ability to exert control over both actions and thoughts. The verb “follow” is active and predatory, suggesting pursuit rather than observationt, blurring the boundary between surveillance and paranoia, so the text itself mirrors the psychological distortion the Party intends to produce. The second-person address “you” directly implicates the reader, creating an accusatory tone that positions the subject as already guilty.

The capitalisation of “BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU” reinforces the omnipresence of the Party, making every citizen feel constantly observed and unable to escape the regime’s power, and appears visually authoritarian, as it’s almost like the party is shouting the statement at you. The surveillance fosters a climate of fear, where self-policing becomes internalized, effectively crushing dissent and ensuring absolute conformity.

The poster becomes a powerful symbol of how totalitarian regimes weaponise imagery and repetition to shape the psychological environment in which individuals live - the feeling of being watched even in moments of supposed privacy demonstrates how the Party blurs the boundary between public and private space, creating a state of paranoia that conditions people to regulate their own behaviour: Orwell constructs a world where fear is not merely imposed from above but absorbed into the fabric of everyday life.

2. ‘Nothing remained of his childhood except a series of bright-lit tableaux… occurring against no background and mostly unintelligible.’

The noun phrase “bright-lit tableaux” evokes static and theatrical scenes - his childhood is artificial, posed, and frozen, implying that Winston’s memories lack narrative continuity or emotional authenticity.

“Bright-lit” is paradoxical: the brightness exposes the images, but in doing so emphasises their emptiness and lack of depth, as they occur against a lack of spatial and temporal anchoring “against no background,” suggesting a complete erasure of context as his memory has been hollowed out rather than merely forgotten.

The quote embodies Orwell’s warning about history’s vulnerability to manipulation: by erasing personal memory, the Party erases personal identity; by erasing collective memory, it erases cultural identity. The fragmented syntax mirrors Winston’s fractured consciousness as totalitarianism has infiltrated his mind,.

3. ‘WAR IS PEACE. FREEDOM IS SLAVERY. IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH’

These slogans rely on stark parallelism and the juxtaposition of opposing concepts to collapse meaning into contradiction. The short, declarative sentences mimic the rhythm of propaganda chants, designed to be memorised rather than questioned - they want the citizens to replace logic and critical thought with blind ideological obedience by accepting these obvious contradictions as reality.

These slogans originate from “The Party,’ and are written in massive lettering across the white pyramid of the Ministry of Truth, which is an ironic placement, given that each slogan is a blatant contradiction. Their presence on an official government building, especially one dedicated to “truth,” implies that within this society such contradictions are not only accepted but treated as foundational principles. These mottos are the first of many oppositions embedded throughout the text, and they reveal the ideological mechanisms that hold Oceania together by making opposites function as equivalents.

Orwell deliberately introduces the novel with these slogans to familiarise the reader with the idea of Doublethink, the mental process that allows citizens to accept two contradictory beliefs at once. The Party cultivates this mindset by stripping individuals of independence, autonomy, and critical thought, and by maintaining an atmosphere of fear through relentless propaganda in order to weaken rational judgement and condition people to accept (and even wholeheartedly believe) statements that defy logic.

4. ‘A tremor had gone through his bowels. To mark the paper was the decisive act’

The visceral imagery of “a tremor had gone through his bowels” immediately grounds Winston’s fear in physical sensation, conveys the deep fear and internal conflict he feels about taking the act of writing in his diary. This physical reaction positions Winston’s anxiety as instinctual rather than intellectual — the threat of punishment has infiltrated his nervous system, demonstrating how totalitarian control embeds itself within the body.

The phrasing “to mark the paper” reduces the act of writing to its simplest mechanical gesture, stripping it of literary flourish or emotional weight. Yet Orwell then frames this act as “the decisive act,” elevating the simple physical marking into an act of immense symbolic defiance. The juxtaposition between the plainness of the act and the enormity of its significance reflects how fraught everyday actions become in Oceania. Even the smallest expression of individuality carries existential risk, showing how the Party has weaponised silence and thought itself.

This moment represents Winston’s first concrete step toward reclaiming personal agency, even though it seems trivial. By giving physical form to his private thoughts, he asserts a fragile autonomy in a world designed to obliterate individuality, yet it is difficult for him to reclaim his identity in a society where the mere act of writing is enough to trigger physical terror.

5. ‘Whether he wrote DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER, or [not], made no difference’

The conditional construction “whether he wrote… or not” immediately reduces the act of rebellion to a binary that the narrative dismisses as inconsequential. The phrase “made no difference” carries a tone of resignation, suggesting that Winston’s fate is predetermined regardless of his choices.

This ironic contrast between the bold typography in the capitalisation of “DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER,” and Winston’s defeated tone reflects the psychological landscape of Oceania, where dissent is both desperately desired and understood to be hopeless. The language reveals Winston’s internal conflict - he cannot stop himself from writing it, yet he believes the Party has already predicted and neutralised the act before he performs it.

The line exposes how tyranny crushes resistance not just through punishment but by convincing individuals that rebellion is meaningless. Winston continues his act of defiance despite believing it will have no impact, illustrating the tension between innate human longing for self-expression and the suffocating pressure of authoritarian control. Orwell uses this moment to show that the Party’s power lies not only in surveillance, but in shaping the very way citizens perceive the value of their own actions.

6. ‘When there were no external records that you could refer to, even the outline of your own life lost its sharpness’

The metaphor of one’s life losing “sharpness” likens memory to a blurred image, suggesting that Winston’s sense of self is becoming visually and emotionally indistinct as only the vaguest contour of his identity remains intact, lacking the detail and solidity that give a life meaning. This reduction of selfhood to a faint sketch shows the profound psychological impact of living under a regime that systematically erases history.

The phrase “no external records” highlights the Party’s deliberate destruction of objective reality, leaving individuals without any fixed points against which to measure their own memories. Without external verification, Winston is forced to rely on impressions that feel increasingly unreliable.

This erosion of personal history reflects the broader destabilisation of truth that defines Oceania. When facts can be rewritten at will, the individual can no longer form a stable understanding of their own past.

7. ‘The Party was the guardian of democracy, to forget whatever it was necessary to forget, then to draw it back into memory again at the moment when it was needed, and then promptly to forget it again’

The irony in this statement lies in the fact that the Party claims to be the "guardian of democracy" (a figure usually connoting care, viigliance and moral integrity), yet here it is applied to an institution whos role is to manipulate the truth and control what people can remember. The act of selectively forgetting and then “re-drawing” memories exemplifies the Party’s systematic rewriting of history to maintain its power.

The repetition of the verb “to forget” constructs memory as an action that must be performed on command, transforming forgetting from a natural mental lapse into a compulsory political duty that mirrors the Party’s continuous rewriting of history. Memory becomes a fluid commodity, emptied of truth and repurposed according to the moment.

Orwell uses this irony to critique how authoritarian regimes can use the guise of democracy to justify oppressive control, while continually manipulating the memories and perceptions of the populace to maintain dominance.

8. ‘We’re destroying words—scores of them, hundreds of them, every day. We’re cutting the language down to the bone’

The gruesome imagery of “cutting the language down to the bone” evokes a disturbing image of dissection or butchery, implying that something once alive is being stripped to its skeletal core. The metaphor of cutting language down to its core suggests a deep and invasive act of control, reducing communication to its most basic, manageable component in order to narrow the cognitive space available for dissent and emotion.

The tricolon, “scores of them, hundreds of them, every day” emphasizes the relentless, ongoing nature of this assault on language. This relentless destruction of words serves as a means to limit individual thought, ensuring conformity and preventing any form of rebellion.

Through this imagery, Orwell shows how the destruction of words ultimately leads to the destruction of thought. When people no longer possess words for complex ideas, the ideas themselves become impossible to conceive: ie people can not even concieve of rebellion, much less enact it.

9. ‘In the end the whole notion of goodness and badness will be covered by only six words - in reality, only one word’

The juxtaposition of “goodness” and “badness” (concepts that contain vast moral and emotional complexity) being reduced to just one word demonstrates the Party’s effort to simplify and control complex moral concepts. The idea that these dichotomies will eventually be collapsed into a single word highlights the totalitarian regime’s goal to eliminate personal thought and moral ambiguity into a single, state-approved term.

It is not enough for citizens to act correctly; they must only be able to conceive of correctness in Party terms. Language becomes the medium through which ethical reality is rewritten.

Orwell exposes how dangerous it is when vocabulary becomes the property of power. By controlling the language of morality, the Party controls the experience of morality. The reduction of words becomes the reduction of conscience - individuals cannot question injustice if they lack the words to describe it.

10. ‘Until they become conscious they will never rebel, and until after they have rebelled they cannot become conscious.’

This sentence is structured as a perfect paradox, with its mirrored clauses creating an intellectual trap. The repetition of “conscious” and “rebel” binds the two conditions together, showing that each depends on the other while simultaneously preventing the other from occurring.

Here he alludes to the notion of class consciousness outlined by Marx (see image on the right), where the working class (the proletariat) needs to become conscious of their exploitation by the bougeoise (the capitalist high class) and overthrow them in order to be free.

The language exposes the clever architecture of the Party’s oppression. The proles, though numerically powerful, are rendered impotent not through violence but through a lack of awareness. By withholding education, history, and political understanding, the Party ensures that the conditions necessary for rebellion never arise. The structure of the sentence itself (looping endlessly) mirrors the lived experience of the proles, who exist in a perpetual state of unconsciousness.

Orwell uses this paradox to highlight how power can be maintained not only by force but by shaping the mental environment in which people operate. When individuals lack the vocabulary, knowledge, or critical framework to recognise oppression, resistance becomes impossible.

11. ‘You could not have pure love or lust nowadays ... Their embrace had been a battle, the climax a victory ... It was a political act’

The metaphor of “embrace” as a “battle” and “climax” as a “victory” uses miltarisitc language to refram personal affection as an act of struggle, presenting physical connection as something combative and oppositional, where a moment of pleasure becomes a symbolic triumph. The diction suggests that even human instinct has become politicised under the Party’s regime.

Winston and Julia’s sexual relationship, framed as a political act, is a metaphor for their resistance to the Party’s control over personal life. The metaphor emphasizes that in Oceania, even love or lust is corrupted and distorted into a form of rebellion against the Party’s ideological purity, illustrating how deeply the Party has infiltrated and warped the most intimate human experiences.

Orwell uses this language to demonstrate how totalitarian power attempts to sever the most fundamental human experiences, turning love itself into rebellion

12. ‘They can’t get inside you. If you can FEEL that staying human is worth while (…) you’ve beaten them’

The metaphor “get inside you” evokes a sense of psychological invasion, suggesting that the Party aspires not only to control behaviour but to infiltrate consciousness. Julia’s assurance that “they can’t” reflects her belief in an inner realm of selfhood that remains beyond the Party’s reach.

The capitalisation of “FEEL” foregrounds emotion as the last bastion of humanity, emphasising that affect (emotion), rather than action, is the true site of resistance.

Orwell uses this statement to show the precariousness of inner freedom in a world where external freedoms have been annihilated. The Party’s power lies in its attempt to reshape thoughts, desires, and beliefs, yet moments like these suggest that identity can still flicker in hidden spaces. This makes Winston’s later betrayal even more devastating: it is the collapse of the very internal refuge Julia insists cannot be breached

13. ‘Do it to Julia! Do it to Julia! Not me! Julia! I don’t care what you do to her. Tear her face off, strip her to the bones. Not me! Julia! Not me!’

The repetition of “Do it to Julia!” and “Not me!” creates a frantic, staccato rhythm that mirrors Winston’s psychological rupture and his desperate speech as he becomes overwhelmed by terror.

The grotesque imagery of “tear her face off” and “strip her to the bones” is shockingly vivid, illustrating the extent to which torture has overridden his humanity as he abandons all emotional loyalty in favour of self-preservation.

The repeated invocation of Julia’s name juxtaposes his former love with his immediate betrayal, highlighting the violent severing of emotional bonds under extreme duress. The dialogue no longer reflects Winston’s beliefs or values, but the total domination of fear. Orwell uses the extremity of the imagery to demonstrate how the Party’s methods force individuals to violate their deepest convictions, leaving them morally hollow.

The repetition of "Julia" emphasizes Winston’s desperation and self-preservation, highlighting the depth of his betrayal. His anguished plea reflects the psychological manipulation and torture that have forced him to prioritize his survival over his love for Julia.

This moment marks the point at which Winston is psychologically broken. By making him wish suffering upon the person he loves most, the Party succeeds in destroying the foundations of his identity. The language shows that the aim of torture is not confession but transformation, the remaking of the self into something loyal only to authority. Winston’s betrayal signifies the complete triumph of totalitarian power over the human spirit.

14. ‘He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother.’

The irony in this statement lies in Winston's "victory over himself," as the reader understands that this victory means his complete psychological submission to the Party.

The phrase “he loved Big Brother” is paradoxical, as Winston had once rejected the Party and desired freedom from its control. The verb “loved,” once associated with Julia and emotional freedom, is now repurposed to signify unconditional devotion to the regime as result of intense psychological manipulation and torture, reflecting the complete erasure of his personal thoughts and desires.

This final line closes the narrative with a portrait of total submission. Winston’s internal world has been so thoroughly dismantled that the Party’s ideology has replaced his emotional truth. The transformation is complete: the man who so desperately sought freedom and defiance now experiences complete and utter devotion to oppression as genuine emotion.

Orwell leaves the reader with the unsettling realisation that absolute power does not merely control behaviour but it can reforge the human soul.

Looking for some extra help with your 1984 essay?

We’ve got an incredible team of English tutors at Pinnacle Learners!

If you’re studying 1984 for your Common Module, we’ll help you strengthen your essay writing and build the confidence to ace your next assessment.

Our one-on-one lessons are available online or in person at our office in Rozelle, giving students across Sydney’s Inner West (Balmain, Leichhardt and beyond) the support they need to excel.

Over the years, our students have boosted their results by 20% or more through expert guidance, proven strategies, and mentoring that goes beyond the textbook.