The 6 Elements of Tragedy in Othello

Shakespeare’s Othello is often described as one of the purest examples of tragedy in the Western canon. But why? The answer lies in Aristotle’s Poetics (4th century BCE), which defined tragedy as the downfall of a noble hero through a fatal flaw (hamartia), often accompanied by excessive pride (hubris), leading to a reversal of fortune (peripeteia) and a moment of recognition (anagnorisis).

The purpose of tragedy, according to Aristotle, is to provoke pity and fear in the audience, which are then released through an emotional purging (catharsis).

Othello fits this tragic model almost perfectly. Below, we’ll explore each Aristotelian element in detail, showing how Shakespeare dramatizes them, and how you can use this framework in your essays.

1) The Tragic Hero

A tragic hero is a hero that had the potential to be great, to go on a hero’s journey and be successful and obtain a happy ending, however due to others manipulation (here Iago) or one’s hamartia, fails and generally dies in regret. The tragedy lies not only in their downfall, but in the recognition that their suffering is both inevitable and self- ragic heroes typically come from a noble or high-status background because their fall from greatness evokes a stronger sense of pity and fear, making their downfall more impactful and their loss more significant to both the audience and society.

Othello begins as the “valiant Moor,” admired for his military service and eloquence before the Venetian Senate. His storytelling wins Desdemona’s love, and his authority makes him central to the Venetian state.

Tragic heroes like Othello often come from a noble or high-status background, as their elevated position makes their downfall more devastating and heightens the audience’s sense of pity and fear. Othello’s initial status therefore deepens the tragedy of his fall - he has the potential for greatness, both as a general and as a husband, but is ultimately undone by his own flaws.

Yet he is also an outsider: a Black man in a predominantly white, Christian society. His nobility is therefore fragile, resting on reputation and trust.

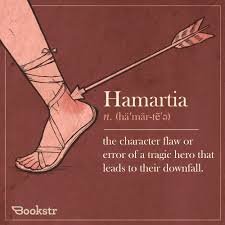

2) Hamartia

Also known as the ‘fatal flaw,’ the hamartia is the error in judgment that leads to a tragic hero’s downfall. It is not necessarily a moral failing, but rather a human imperfection - a misjudgment, weakness, or excessive trait (such as pride, ambition, or jealousy) that causes the hero to make a critical mistake. This flaw sets in motion a chain of events that ultimately results in a catastrophe, making the hero’s fall both inevitable and relatable.

Othello, arguably, has multiple hamartias

Definition of hamartia - an ‘Achilles heel’

His credulity and trust: his readiness to believe Iago stems from his trusting and honourable nature, a trait that once made him an effective leader but leaves him vulnerable to deceit. He is overly trusting and believes Iago (to a fault)

His insecurity: he is aware of his difference and outside status. As an older, Black outsider in a white, aristocratic society, he fears that Desdemona’s love is unstable or undeserved, which makes him more susceptible to Iago’s insinuations. His belief in Desdemona’s infidelity stems from his own feelings of insecurity, as he believes his race renders him inferior.

His ‘rationality’: his demand for absolute proof reflects his soldier’s mindset, and he seeks tangible, visible evidence (“ocular proof”) as he would in warfare, mistaking Iago’s manipulations (Cassio’s laughter, the handkerchief) for objective truth.

Thus, his qualities that are initially admirable (his kind nature, trust and honourability) are tragically distorted under emotional and social pressure. Shakespeare uses this transformation to expose the fragility of human reason and the ease with which virtue can become vice when guided by insecurity and manipulation.

3) Hubris (Excessive Pride)

Hubris (which is defined as excessive pride or self-confidence) is a defining feature of the tragic hero and a key cause of their downfall. It represents the hero’s fatal overestimation of their own power or judgment, leading them to defy moral or divine order in pursuit of what they believe is right. This arrogance blinds them to truth and reason, bringing about their inevitable destruction and evoking catharsis in the audience, who witness the hero’s fall from greatness.

Othello’s hubris emerges in his conviction that he has both the right and the moral authority to judge and punish Desdemona: “Yet she must die, else she’ll betray more men.” His pride blinds him to justice and reason, transforming him from noble general to self-appointed executioner. This same arrogance is evident in his belief that his judgment is infallible, even when it rests on fragile evidence (a handkerchief and Iago’s insinuations)

In believing himself incapable of error, Othello tragically becomes the architect of his own ruin - he is undone by the very traits that once defined his greatness.

4) Peripeteia (Reversal of Fortune)

Peripeteia refers to the reversal of fortune, the moment in tragedy when the hero’s rising success collapses into inevitable downfall. In Shakespearean tragedy, this reversal rarely occurs in a single instant; rather, it unfolds gradually through a sequence of degradations that strip the hero of dignity, reason, and moral clarity. In Othello, this process is vividly embodied in Othello’s transformation from noble general to a broken outcast.

Once a figure of military authority and composure, Othello’s jealous rage manifests physically in seizures and fits, a stark contrast to his earlier calm when defending himself before the Senate, a symbol of his psychological disintegration.

In spying on Cassio, Othello literally and figuratively lowers himself. The once-commanding general is reduced to a furtive observer, eavesdropping on Iago’s deceitful performance, restricted to the margins of the stage (and the narrative).

Othello’s eloquence (his defining mark of nobility) deteriorates as his speech fragments into short, impulsive bursts that echo Iago’s rhetoric. The shift from controlled blank verse to chaotic prose reflects the collapse of reason and identity.

His blasphemous exclamation, “Zounds!” signals a rupture of moral and spiritual order, as he transgresses divine law and curses God

When Othello exits crying “Goats and monkeys!”, he embodies the animalistic imagery Iago once used to degrade him. The transformation is complete: Othello becomes the monstrous figure he feared, internalising Iago’s racist projections.

His public slap of Desdemona and the moment he gives Emilia money for her “pains” (ie treating her like a mistress of a brothel) mark the ultimate perversion of love into violence and lust. What began as devotion ends in degradation, as Othello reduces Desdemona to an object of scorn.

5) Anagnorisis

Anagnorisis is the moment of recognition or revelation in tragedy - the point at which the hero moves from ignorance to knowledge, understanding the true nature of their situation and their own fatal error. In classical tragedy, this moment is profoundly ironic: it comes only after the hero’s downfall has become irreversible, intensifying the emotional impact of the play.

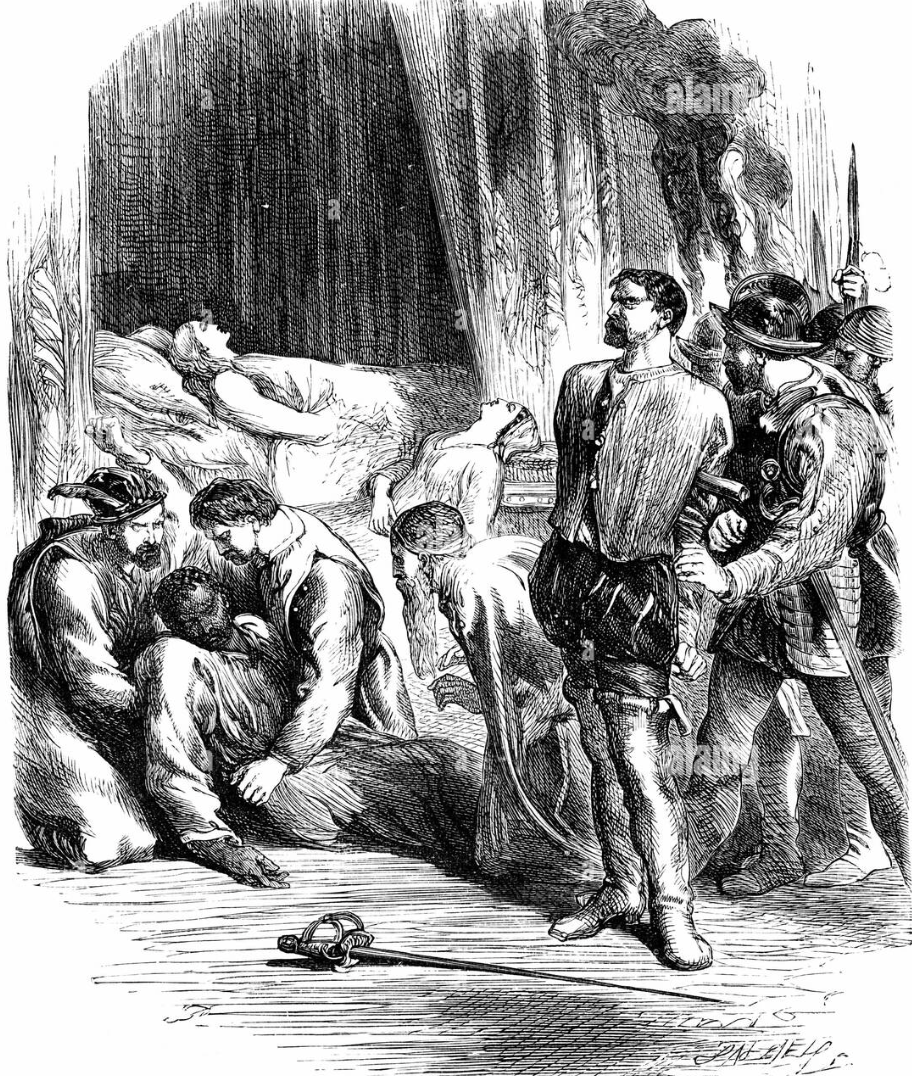

In Othello, this moment occurs after he murders Desdemona and learns of her innocence and Iago’s deceit. This recognition transforms Othello’s ignorance into tragic awareness, fulfilling the Aristotelian ideal of anagnorisis as the awakening of knowledge through suffering. His self-reflection “one that loved not wisely but too well” encapsulates the bitter irony of his downfall: the same passion that once defined his nobility (ie his love for Desdemona) and depth of feeling becomes the force that drives his destruction.

This moment of clarity does not redeem Othello but deepens the tragedy, as he finally understands the magnitude of his error when no restitution is possible. The audience’s pity and fear reach their height here, as we witness a man of once-great virtue attain truth only through loss, his enlightenment arriving at the precise moment when it can no longer save him.

6) Catharsis

Catharsis is the emotional purification or release experienced by the audience through the unfolding of a tragedy. According to Aristotle, tragedy should evoke pity and fear (pity for the suffering of the innocent and fear that such downfall could befall anyone), and through these emotions, the audience achieves a moral and emotional cleansing and purging through the hero’s downfall.

In Othello, catharsis arises from the devastating contrast between Desdemona’s purity and Othello’s corrupted perception of her. We pity Desdemona’s innocence and fidelity, and we fear the consuming power of Othello’s jealousy, a passion that transforms love into violence. His final act of suicide functions as both punishment and release: Othello takes responsibility for his crime, seeking to restore a sense of moral order, but his recognition arrives too late to undo the tragedy.

For the audience, this moment generates a profound cathartic response (a mingling of sorrow, horror, and understanding). As Othello dies, we are left with both grief for what is lost and insight into the destructive potential of pride, jealousy, and misplaced trust. In this recognition, the emotional intensity of tragedy becomes a form of renewal: through Othello’s ruin, the audience confronts and purges its own fears about the fragility of human virtue.

Need Help Understanding Shakespeare’s Othello?

Our incredible team of English tutors can help!

At Pinnacle Learners, we teach students how to use frameworks like Aristotle’s tragedy to structure stronger essays, connect ideas to the text, and impress markers in their Othello essays

Our one-on-one lessons are available online or in person at our office in Rozelle, giving students across Sydney’s Inner West (Balmain, Leichhardt, Annandale, Birchgrove and beyond) the support they need to excel.

Over the years, our students have boosted their results by 20% or more through expert guidance, proven strategies, and mentoring that goes beyond the textbook